Explorative Approach Is Moving!

I’ve moved Explorative Approach to a host with it’s own domain. Since my programming skills are non-existant, I’m still struggling with setting up the site and getting the design right. My plan is to get most of the tweaking done by the end of the week so that I can concentrate on new updates, posts and experiments again.

The blog is reachable and usable at the new location already, even though it’s still plain to see that it’s not final.

The new main adress is: http://explorativeapproach.com/

You can also reach the blog via: exap.net

I’m very happy to have already found a small but steady stream of visitors to this blog and I hope you’ll all come check out the new version as well. Feedback and comments on the move and the new design are welcome, of course. And help. Help is very welcome right now. :P

You can reach me at shane(at)exap.net

See you there!

Regards,

Shane

Task-Managing Series, Part 2: Optimal Method

It has now been three weeks since I started the task-managing experiment and I have mainly been focusing on when and how to set my tasks. Here are my experiences, so far:

—

Ongoing List vs. New List Every Day

When I work with an ongoing to-do list, I simply have one list with all the tasks that need to get done and I add tasks and tick tasks off as I go along. If I don’t get a task done today, it will simply still be on the list tomorrow. Similarly, if I have a task I know I need to do in two days time, I simply write it down now, together with all the other tasks.

Stats:

Using an ongoing list and ta-da lists, I completed 17 out of 19 tasks during the course of one week. That is a good ratio, but as you can tell, I didn’t set very many tasks. This is mainly because an ongoing list gets crowded pretty quickly. It’s no real help if you have a list of 20 unsorted tasks in front of you, so with the ongoing list, I only wrote down the most essential tasks. This method required an average of 47 seconds per completed task.

Pros:

This method is very flexible and takes up a minimal amount of time. There is no re-writing of tasks and no scheduling involved. It’s probably the easiest method to follow and the fact that it encourages you to set only a few essential tasks per day can be a blessing.

Cons:

The downside of this method is how chaotic it is. There is no sense of priority and if I set a task today that is meant for a few days later, it will just sit there with all the other tasks for a few days. It makes it difficult to decide what needs to be done first and I rarely got the satisfaction of completing the entire list.

—

The alternative is to start a new list for each day. Following this method, I re-write any unfinished tasks to carry them over to the next day. I update the list as I go along, when new things come up, but I also set aside a specific time during the day for organizing the tasks and setting new ones. I wanted to test doing this either in the morning or in the evening, but I was useless in the morning. In the evenings, I can think clearly about what needs to be done the following day and make a decent task-list. Early in the mornings, my brain just doesn’t want to do this kind of thinking. I can be productive early in the day, but apparently not the planning kind of productive.

Stats:

Following this method (also with ta-da lists), I completed 32 out of 35 tasks during the course of one week. Again, the ratio is good, but this time, I set and completed way more tasks than with the ongoing list. I spent an average of 44 seconds on each completed task, slightly less than with the ongoing list. While the difference is small, it shows that focusing on what tasks to set once a day is probably more efficient than just adding them as they come up.

Pros:

In short, with this method I got more done in slightly less time (per task). That’s certainly a good thing. I found that it really helps me to take a few minutes in the evening, before I turn off the computer for the night, and plan the important tasks for the next day. Since I start with a clean slate each day, the list never gets too crowded and it’s easier to prioritize, even though I didn’t use a system to set priorities. Another positive aspect is that completing the whole list by the end of the day gives me a nice feeling of accomplishment. Plus, re-writing left-over tasks for the next day is like making a renewed commitment and that can help to complete them.

Cons:

I really didn’t find any major drawbacks for this method.

—

Preliminary Conclusion

My experiment is still ongoing and I am currently testing out different media for managing my task-lists. So far, I can conclude that making a new list for each day is definitely better than using an ongoing list. An ongoing list is extremely simple, lacking structure, prioritization and scheduling. This might be a good thing if you have the tendency to over-organize and want to categorize every minute detail. An ongoing list could help you focus on just what’s relevant. For any other situation, I recommend taking some time evening to plan the tasks for the next day.

While I set and completed more tasks with a new list each day, keep in mind that not all tasks are created equal. “Take out the trash” and “work out” both count as one task, but one of them is completed in under a minute while the other takes about an hour. Also, not every task is equally relevant. In this early stage of my experiment, I have not yet done anything to prioritize my tasks, but I will be looking into that later on.

The findings of this first part of my experiment aren’t particularly spectacular – I’m aware of that. Stay tuned for my next update, when I will be reporting on the different types of task managing software I have used.

This post is part of a series.

Part 1: Introduction to the Experiment

Part 2: Optimal Method

The Slump: A Crucial Factor to Building New Habits

Building habits is key to personal progress and success. If you manage to continually build new, positive habits that increase your productivity, your skills or your happiness, then you are obviously on a fast track to a wonderful life. But, as you probably know, it can be very challenging to build a new habit up to the point where it is truly integrated into your life. Think “Motivation” – a theme absolutely pivotal to almost every book, blog, seminar and system concerned with self-improvement. After all, it’s not that we don’t know what’s good for us. We know perfectly well that we should get our asses of the couch and do that workout, finally clean out that messy drawer and finish that project that’s been at the back of our minds for so long.

But somehow, we can’t get ourselves to get up and do it. Somehow, there is just too much inertia and it can seem impossible to overcome. And so, we make an exception and don’t do the workout today. Soon, the exception becomes the norm, the guilt diminishes and what once was an exciting new part of our lives somehow fades and disappears.

—

Presentism

Have a quick look around the producto-blogosphere on the subject of motivation. You can find countless posts on how to make motivation a breeze – if there’s one thing there isn’t a shortage of on the internet, it’s X-point lists on how to take all the effort out of self-motivation. I am not going to contribute to that collection in this post, because while I have one piece of very valuable advice when it comes to motivation, I can’t say it’s easy to follow.

The root of the motivational problem lies in psychological presentism. Presentism is caused by the fact that whatever we think about, we always use our present situation as a starting point. All our thoughts, be they of the future or the past, of things close or far away, are always distinctly influenced by what’s here, now. This is why it’s difficult to think of what you would like to eat when you are full. How does presentism apply to motivation? Let’s take exercise as an example. Let’s say you read an inspiring article or a book about all the benefits of exercise and you decide to get started with a regular workout routine. In the beginning, you’ll no doubt be very excited and enthusiastic about it, reading up on tips for your workout, perhaps buying new running shoes, some dumbbells or a heart rate monitor. The first few workouts go very well and you feel fantastic afterwards. You picture how much better your life will be from now on and how great it will be to lose some weight, become more athletic and attractive etc, etc. In this state of enthusiasm, it’s very difficult to imagine that you’ll ever be unmotivated.

But then it happens: One morning, you wake up feeling pretty squashed and you just can’t get yourself to go for that run or to lift those weights. You’re having a terrible day and there’s just too much work to do to squeeze in a visit to the gym. Your muscles are sore, there’s that weird pain in your shoulder and your motivation reaches an all-time low. In this new emotional state, it’s difficult to imagine why you would be excited or enthusiastic about the prospect of working out several times a week. Isn’t it all just futile effort? After all, you’ve hardly lost any weight and looking in the mirror, you still don’t resemble anything you’d expect to see on the cover of a glossy magazine.

This is the point where many conclude that they have somehow “lost it”, that they have failed or that the whole thing was a bad idea to begin with. Sometime later you come to regret that you stopped, you see regular exercise in a positive light again and, perhaps, the whole process starts over.

—

Know The Slump

Here’s the thing: This will always happen. You will always lose your initial momentum, you will always find yourself unmotivated, you will always experience this slump, when you start something new. Whether it’s exercising regularly, launching a community project, writing a blog or starting a new business, the slump is all but unavoidable. No matter what you do, there will always be a tendency for everything to return to the way it was before (this is known as homeostasis).

So, what can you do about this? As I have already stated, I can’t offer you an easy solution. Here are two things that can help anyway (they help me immensely):

1. Anticipate it.

Know that there will be times when you won’t feel like sticking to your plan at all. Expect to be unmotivated at some point in the future. This way, it will not take you by surprise and you will not feel like this is the end of everything. Instead it’s just part of building the new habit and it you knew it would happen. This can be likened to knowing that you’ll get a jab when you visit your doctor. It will still hurt, but you knew it would happen and you realize it’s part of the process of getting healthy again.

2. Grit your teeth.

This is where discipline comes in. Sometimes, it’s not about getting yourself motivated, sometimes it’s just about gritting your teeth and doing it, despite not being motivated. Find a personal mantra that helps you override your emotional response and reminds you of your discipline. My mantra for such situations is “my discipline is my freedom”, but I guess I’ll have to explain the background to this in another post. Remind yourself that you made the decision to stick with this new habit when you were feeling good and had thought clearly about it. Now, in your negative emotional state, it is not the time to make new decisions because those decisions would be greatly compromised by your mood.

—

Good News

As you have probably guessed by now, I myself have gone through the cycle of starting a new habit, experiencing the slump, quitting, regretting it and starting again, many, many times. I’ve also seen my friends go through this cycle countless times and from my work as a martial arts instructor, I know that virtually every new student experiences the slump within the first six months after they start.

The good news is that the slump is very predictable and that it’s usually nonrecurring. It’s predictable because it almost always strikes within a few months of beginning something new. Depending on factors such as social and monetary commitment (if you pay for it, and told all your friends, you’ll last a bit longer) and frequency (something you do daily will lead to the slump more quickly than something you do once a week), the slump can occur sooner or later, but if I had to narrow it down, I’d say you’ll experience the slump at some point between the 10th and 20th time you repeat the new behaviour. And if you get through it, sticking to your new habit, that will have been the worst of it. I’ve never experienced a second slump as bad as the first one and the longer I continue with a new habit, the further apart the following “mini-slumps” are.

Getting back to the example of regular exercise, you can rest assured that if you keep going and drag yourself through that slump, then after just a few workouts fuelled by discipline alone, you’ll see a light at the end of the tunnel, your motivation will return and you will be much, much closer to having acquired a new habit.

By all means, learn about all the possibilities you have to get yourself more motivated, but never forget to anticipate the inevitable slump and when all self-motivation fails, remember: This is part of the progress, you can fight this thing with your willpower and you will come out the other side a stronger and happier person.

Fool’s Plight: The Dunning-Kruger Effect

(Total reading time: < 4 minutes)

The Dunning-Kruger effect is a cognitive bias that warps our ability to judge our own competence. To put it very bluntly, stupid people tend to think that they are quite brilliant, because they are too stupid to tell that they are, in fact, stupid.

(Don’t worry, I know it’s a bit more subtle than that.)

The effect is named after Justin Kruger and David Dunning, who discovered it by doing a series of tests, after the completion of which the participants were asked to guess how well they think they did. The participants were also asked to evaluate their general skill in the tested subject. For example, taking part in one of the experiments, you would have first completed a written test of logical reasoning, similar to an IQ-test. You would then have been asked to guess how well you did in this particular test and also asked to evaluate how good you generally are at logical reasoning.

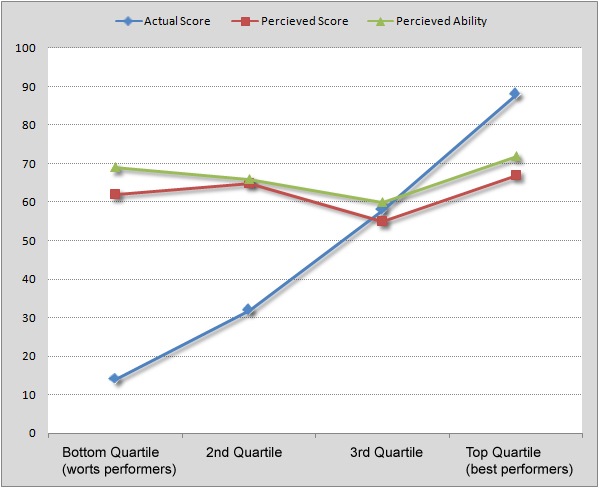

Here is what the results of the study looked like:

In the graph, the results are sorted by how well the participants actually did in the test, as we can see from the Actual Score plot steadily rising from left to right. A minor effect that can be seen is that practically everyone evaluates their own ability as being slightly better than their test scores indicate. Basically, everyone is saying “I might have made a few mistakes in this test, but generally, I’m pretty good at this”.

By far the more dramatic effect however, is that most participants dramatically misjudge their abilities. For starters, everyone thinks they are better than average (>50), an effect also known as Illusory Superiority. As we can see, the worst performers’ estimation of their own skill is quite similar to the best performers’ estimation. It seems that those who actually are of slightly more than average skill have the most realistic assessment of their own skill. The best performers underestimate themselves, which might be partially due to modesty.

Dunning and Kruger state that the cause of the effect is that incompetence at a certain skill also robs one of the ability to make an accurate judgement concerning that skill. This, coupled with the tendency to protect one’s feeling of self-worth (a tendency every healthy person displays) inevitably leads to the crass overestimation shown in the study.

If you would like to learn more about the studies, I highly recommend this post on Pro-Science. It even includes a link to the original research-paper, which you can download.

—

Practical Examples

In the opening paragraph, I made the very condescending statement that stupid people are too stupid to recognize their own stupidity.

This is true, but you have to keep in mind that we are all stupid at some things. I know that I’ve experienced the DK effect myself several times. I have often underestimated the difficulty and complexity of a task (and therefore also my expected skill at it), before I knew much about it. Maybe the “I’d be pretty good at that/I bet that’s easy”-effect is a mild version of the Dunning-Kruger effect. Have you encountered any of the following, thinking them yourself or hearing someone make a similar statement?

- Photography is really easy. It’s not like painting or drawing, where the artist actually has to do something.

- It must be great to be a novelist, all they have to do for a living is tell stories.

- I can’t believe how crappy this movie/videogame/comic/website is! Even I could do better than that.

- Of course, once you get into serious photography, try to write a book or make a movie, videogame, comic or website, you’ll encounter a whole new world of complexity and difficulty and as you progress, you become more humble.

Another example of the DK effect is very familiar to me from martial arts training: Many students of martial arts become overconfident after about eight to twelve months of training. With some, but only very little, experience under their belt, they tend to think they are invincible and could take on almost anyone. This is the time when they are also most likely to give tips to others, correct them and otherwise try to help them. After a while, if they keep training, this usually settles and they realize that there is still a lot to learn.

—

What Can I Learn from This?

The DK effect is certainly very interesting, but is it also useful to know about? First of all, I believe knowledge of the effect can help you avoid falling for it. As described in some of the work done by Dr. K. Anders Ericsson, experience is a pretty good indicator of skill. So instead of asking yourself “How good am I at this?”, ask yourself “How many hours have I put in?”. If the answer is “dozens” or “hundreds”, then it’s unlikely that you are already very skilled. If, however, the answer is “thousands”, then it’s more likely that you can trust your intuitive judgement of your own skill.

To me personally, the Dunning-Kruger effect is one of the reasons I want to dedicate most of this blog to exploring and testing, rather than just expressing opinions.

For an interesting philosophical approach to the DK effect, check out this post on ribbonfarm. To see why my testing and exploring might get me nowhere, see this tidbit on the connections blog. I’m not sure if I want to dedicate a post to the subject mentioned there as well.

Flexibility Experiment, Part 4: Q&A with Anne Tierney from Innovative Body Solutions

I have been doing the Resistance Stretching exercises daily for one week now. This method of stretching took some getting used to and I had difficulties with some aspects of the exercises. Luckily, when I contacted Anne Tierney, a Resistance Stretching expert, she generously gave me input and advice. Anne uses and teaches a branch of Resistance Stretching called Ki-Hara, and together with Steven Sierra, she has trained numerous top athletes. Here are a few of my questions about Resistance Stretching answered by Anne:

—

Q&A

Q: For some stretches, I have difficulties because my legs are a lot stronger than my arms (naturally). So when I am pulling my leg into a stretch and resisting it, it’s a huge effort for my arms/upper body. Also, I can never fully resist a leg stretch, because if I did, my leg would just remain contracted. Am I doing something wrong?

A: Yes! You don’t need to resist so hard. The arms will never be able to overpower the legs. Because of the name ‘Resistance’ Stretching people automatically think it means resisting as hard as you can, but really all you need is some resistance, like a 5 out of 10. You want movement! Resisting too hard will not only stress the arms, but it will also cause the joints to lock up, substitution, etc. You do not want to fight yourself – it is a losing battle! It is most important that the resistance is even and consistent.

—

Q: I am still used to traditional stretching, where you stay in the stretched position for a relatively long time. Doing six to ten repetitions of a Resistance Stretch doesn’t take very long and I can’t help but wonder “is this enough?” How important is the amount of time the muscle is in the stretched position for good results, in your opinion?

A: If you do 6-10 repetitions of all 16-17 exercises, you will actually get a pretty good workout and feel like you did quite a lot. In Resistance Stretching, we rarely hold a position and if we do it is with a contraction and only for a few seconds. For the most part we don’t hold the stretches, though. What’s more important is the methodology of why it is working and why holding it there usually just creates an overstretched muscle. Think about it – how many years have you been stretching the “old” way where you claim you “feel” like you are getting more done – 10, 15, 20, 30 years? How flexible do you feel? Has it changed much? (Nope. See first part of the series) If you follow the philosophy of resisting and balancing muscle groups you could easily gain 2 or 3 inches in 10 minutes. Some people haven’t gained that in 10 years of traditional stretching or if they have they have done it at the expense of the integrity of the joints and strength of the muscles.

—

Q: I often think that it would probably be a lot easier to do the Resistance Stretches with a partner pulling me into the stretch, so that I would only need to concentrate on the resistance part. When you work with athletes, do you mainly teach them to do the stretches on their own or do you mainly “work on them”, helping them with the stretches?

A: Yes, obviously getting assisted is the best way possible because you can give more resistance, make more dynamic movement/rotational patterns and just get a lot more done – as in life, a little help goes a long way. However, the ones that we have been most successful with have done a combination of assisted stretches plus working on their own. Because again, as in life – a little hard work also goes a long way! Plus the more they work on their own the more they learn about their own body and and can provide more useful feedback to us. The combination of working on your own and working with assistance is invaluable.

—

Many thanks to Anne for taking the time to answer my questions. You can find more information on Ki-Hara Resistance Stretching on the Innovative Body Solutions homepage, where you can also find Resistance Stretching coaches near you and learn about workshops and upcoming events.

This post is part of the Flexibility Experiment series.

Part 1: The Problem with Stretching

Part 2: Introducing Resistance Stretching

Part 3: Method and Benchmarks

Part 4: Q&A with Anne Tierney, Resistance Stretching Expert (currently viewing)

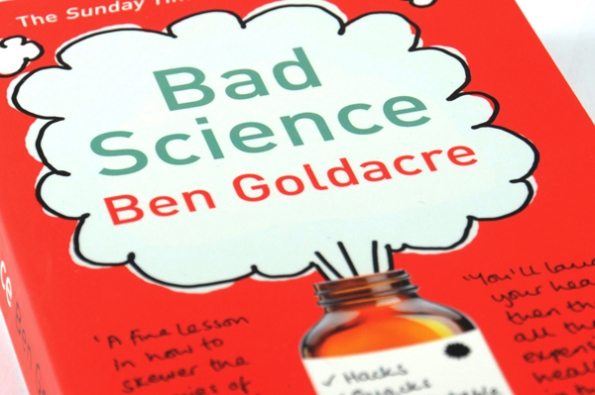

Bad Science by Ben Goldacre: You Must Read It

Bad Science is essentially about what it says on the cover. In it, Ben Goldacre, a Doctor and columnist for The Guardian, rails against the horrible misinterpretation of scientific studies often found in newspapers and TV-shows, makes fun of nutritionists and some of their silly claims and rants about misleading and unfounded health-scares, among other things. In all this, he is not just informative and thorough, but also very funny. Bad Science is a book that I could hardly put down, it was so interesting and so much fun to read.

While the book mainly focuses on medicine and medical science, it’s greatest merit lies in the way it explains and frames the scientific method. In the early parts, the book introduces some fairly basic criteria of what is scientifically sound and what isn’t. It slowly expands on these concepts and by the time you are done with it, you’ll be that much more capable of spotting faulty studies, skewed results and foul statistics yourself. The book also offers the perspective of scientific thought being readily available, easy to understand and basically something anyone can do, anytime. You don’t need a degree or a white lab-coat to apply science – and the fact that science is often portrayed as something exclusive to sophisticated, bearded and bespectacled men is one that Goldacre strongly contests.

What particularly struck a chord with me is one of the mottos that reoccur in Bad Science, which is: “I think you’ll find it’s a bit more complicated than that.” Simple solutions are very tempting, but once you dig a bit deeper, you often find that things are more complex and also more interesting than at first glance. This has been something of a central theme for myself and it is represented wonderfully in Bad Science. When Goldacre digs, he digs deep and with admirable persistence. You can follow some of this wonderful digging on the Bad Science Blog. (Also, you can get the T-Shirt with the above motto here.)

Quite simply, my conclusion is that Bad Science should be required reading for just about everyone – not only because otherwise you might never know enough about Homeopathy to make a smart decision about it, or always remain puzzled when clever people believe stupid things or forever think there is nothing wrong with the claim that certain foods are good for you because they contain a lot of oxygen – but also for the fresh perspective on scientific thought that it offers. Apart from that, you’ll have a good laugh while reading this book, and don’t the say that laughter is the best medicine? Or is that another example of bad science?

You can find the book here on Amazon. For more book recommendations, see my recommended books page.

Mistaken Expectations, Wrong Predictions

How do you decide what restaurant to go to, which movie to see, what pants to wear today? And what about big and important decisions like what career-path to choose, where to settle down and buy a house or whether to have kids or not? To some extent every decision we make is based on predictions. We imagine what an evening at one restaurant would be like versus an evening at a different one and make our desicion based on where we imagine we will have more fun, get better food and other criteria.

Interestingly, there are some systematic mistakes we tend to make when we imagine such future events and this can lead us to making bad decisions. Dan Gilbert is a psychology professor and the author of Stumbling on Happiness, a book that I am currently reading and might have to add to my list of recommended books soon. Watch the video below to see Dan Gilbert talk about how we make decisions and where we go wrong. The video is very much worth seeing, not just for it’s interesting content but also because of Gilbert’s wit and charismatic delivery.

If you enjoyed this and want more, you can watch another TED-talk by Dan Gilbert here (what makes us happy?) or visit his website.

Flexibility Experiment, Part 3: Method and Benchmarks

(Total reading time: <3 minutes)

After illustrating my issues with common stretching exercises (they don’t work) in the first part of this series and introducing the new method I will experiment with (Resistance Stretching) in the second part, it is now time to lay out how I will test the new stretching method and how I will measure it’s effects (or lack thereof).

Method

I will be doing the Resistance Stretching exercises as described in the book The Genius of Flexibility by Bob Cooley. I will do the exercises once a day, at least six days a week for the next 30 days. I’m allowing for one day off per week in case I feel like it might be too much to do the exercises daily, but I assume that won’t be the case. During these 30 days, I will continue with my usual training routines (weight-lifting and martial arts training) and I will not make any major changes to my diet, sleeping schedule or anything else that might affect the results. I also want to emphasize that I will be doing all of the exercises described in the book and only the ones described in the book. In other words, I will not do just the exercises that could improve the benchmark-results (see below).

Benchmark: Objective Measures

I want to be able to objectively measure changes that Resistance Stretching might cause. For this, I picked out a few easily measurable stretches as benchmarks. The stretches were performed after a very light warm up and were measured as seen on the pictures. I didn’t pre-stretch or do any heavy exercise before measuring.

Split

The split, classical representation of Kung Fu-flexibility, has to be a part of this, of course. It also happens to be a special weakness of mine. Even with the most intensive stretching I’ve ever done, I’ve never come close to a full split. To avoid underpants-related variations that might occur with a crotch-to-ground measurement, I measured from the inside of my hip joint to the ground. Result: 46 cm / 18.1”

Sideways Split

The sideways split is a good measurement of leg and hip flexibility, as it involves many different muscle-groups. Here, my current flexibility isn’t quite as abysmal as with the central split. Measured from the inside of the hip joint to ground, I got the same result for the sideways split facing either way: 21 cm / 8.3”

Toe-Touch

This is done with completely straight legs and as a benchmark, I measured the distance from the lowest point of my head, when it was hanging down in a relaxed way, to the ground. On the picture, I have my head lifted slightly, so it doesn’t exactly represent the position that was measured. Distance: 36 cm / 14.2”

Joining Hands Behind Back

Here, I didn’t take any measurements. I simply tried to get my hands as close to each other as possible, without pulling on them. I particularly wonder if I can correct the apparent asymmetry visible here (my right hand can’t reach upward as far as my left hand).

Measurements (overview)

| Centimetres | Inches | |

| Split | 46 | 18.1 |

| Sideways Split, left | 21 | 8.3 |

| Sideways Split, right | 21 | 8.3 |

| Toe-Touch | 36 | 14.2 |

Subjective Impressions

Of course, not every effect of a stretching routine can be measured objectively. Not that I expect it to positively influence every aspect of my life, as Bob Cooley claims it should. But I will take note of and report on what the stretching routine feels like, whether it is easy to keep doing daily and any side-effects that I experience that might be caused by the stretching. Depending on how much happens during the experiment, I will publish one or more posts before the end of the 30 day period.

This post is part of the Flexibility Experiment series.

Part 1: The Problem with Stretching

Part 2: Introducing Resistance Stretching

Part 3: Method and Benchmarks (currently viewing)

Part 4: Q&A with Anne Tierney, Resistance Stretching Expert

Flexibility Experiment, Part 2: Introducing Resistance Stretching

(Total reading time: 5 minutes)

There are two names most widely associated with Resistance Stretching: Bob Cooley and Dara Torres. Bob Cooley is the guy who came up with the technique of Resistance Stretching and Dara Torres, the famed American Olympic swimmer, is arguably the one person who gave it the best PR. According to Torres, Resistance Stretching played an important role in her training and she claims it improved her swimming performance (see this interview). She has even said that Resistance Stretching was her “secret weapon”, implying that it played a very important part in her training.

How Resistance Stretching Works

The principle behind Resistance Stretching is quite simple: You need to be contracting the muscle that you are stretching. Usually, when you are stretching, you get yourself into a position that elongates a specific muscle or muscle-group and try to relax those muscles as you are stretching them. In Resistance Stretching, you will be contracting the muscle while you are stretching it, meaning that the muscle is constantly under full tension as it is being stretched. If it sounds like contracting a muscle while stretching it must be painful, I can tell you right away that surprisingly, it isn’t. It can be pretty complicated, though. Doing Resistance Stretching on your own, you will sometimes have to get into very unusual positions in order to be able to contract a muscle while stretching it.

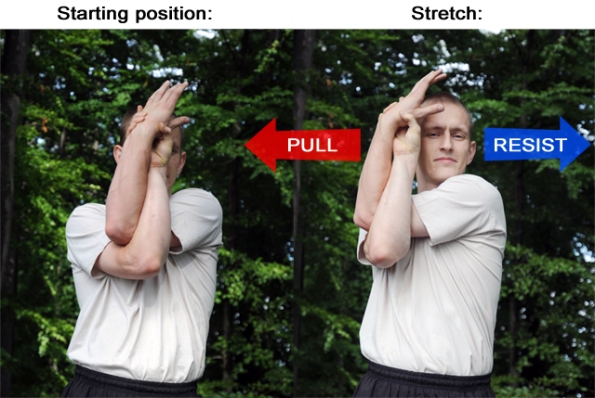

To quickly try out for yourself what Resistance Stretching feels like, you can try this simple stretching exercise for the shoulders:

Position your arms as shown on the left in the image above and use the lower arm to pull the upper arm into the stretch. All the while, push against the direction of the stretch with the upper arm. Now, for this stretching method, you don’t need to hold the end-position for a long time. Instead, release the stretch again after one or two seconds and repeat the process several times. Try to resist the stretch as much as possible, contracting the muscles in your shoulder and back. It takes some getting used to, but this exercise can give you a feel of how Resistance Stretching works and what it feels like. Take a few minutes to try it out now, before moving on to the next section.

Claims and Doubts

I want to point something out, to avoid misunderstandings: I am not a fan of Resistance Stretching. That is not to say that I have anything against it, either, I simply haven’t decided yet. That’s why I am doing an experiment with it. I want to find out whether I can benefit from it or not and whether I like it or not.

I must say, though, that it’s a bit of a strange coincidence that I even got to know about Resistance Stretching. I was randomly browsing shelves in a bookstore and because I had previously spent some time thinking about stretching and flexibility, Bob Cooley’s book The Genius of Flexibility, immediately caught my eye. I went ahead and bought it practically without looking at it’s contents (it was the only book on the subject of stretching on display in the bookstore). Had I skimmed through the contents of the book, I probably would have left it behind and here’s why: Cooley makes many fantastic claims, all of them unreferenced. For example, he claims that “Flexibility increases your self-esteem, self-worth and self-respect” and also that “Flexibility shows you how to be more conscious of what you truly desire”. Those are just two among many, many such claims in the book. Now, I wouldn’t mind so much if these claims were based on anything non-anecdotal. I just like my wild claims to come with references to controlled trials, I guess. It’s also worth mentioning that Resistance Stretching is also referred to as Meridian Stretching and that it’s built around an elaborate system of different stretching exercises connected to your body’s energy meridians as defined by Traditional Chinese Medicine. Again, I don’t principally have anything against TMC or making such connections, I just don’t like to see them simply made up by someone rather than based on solid research. In short, what I dislike about the book is it’s woo-wooiness.

Still, I have the book and I might as well try it out before dismissing it. I believe that the techniques described can be very effective, even if the theory behind them is off-track (so there shouldn’t be much of a nocebo-effect going on when I do the experiment on myself).

Why Not Solid Science?

You might be wondering now, why I don’t do a stretching experiment based on more solid scientific claims, if I have such a problem with the esoteric aspects of Resistance Stretching. On the one hand, I have been doing all kinds of other stretching exercises for years and they don’t work for me, as illustrated in part one of this series. The other reason is that I have so far not found any particularly helpful research on the subject of stretching. Generally, the research focuses on health benefits of stretching, mostly injury prevention. If you’ve ever read a fitness-magazine, you’ve probably seen articles quoting studies as either showing some benefit of stretching or as showing no effects or negative effects of stretching. Your typical fitness-magazine will basically run these two stories alternately – “The Five Best Stretching Exercises” in one edition and “The Truth Behind Stretching: Why it’s actually bad for you” in the next. For some examples, see this article claiming stretching to be beneficial for muscle growth and this article claiming stretching to be detrimental to performance.

A systematic review done in 2003 came to the interesting conclusion that: “Due to the paucity, heterogeneity and poor quality of the available studies no definitive conclusions can be drawn as to the value of stretching for reducing the risk of exercise-related injury.” [italics mine] You can find the abstract for this review here.

So, in short, this self-experiment is not based on available scientific research because I could not find any really helpful scientific research on the subject of stretching. Suggestions welcome.

Why Stretch at All?

If stretching may do little or nothing to prevent injuries and it doesn’t even make you flexible beyond after an initial boost, should anyone bother with it at all? The argument can be made that if you have a “normal” range of motion, you should just ditch stretching all together. I certainly know a few people who are fairly athletic and never or almost never do any stretching and it doesn’t seem to be doing them any harm.

For me personally, there are two reasons for stretching: First, many stretching exercises, especially those derived from Yoga, just feel good to do. During the exercises and for a while afterwards, it just feels like I’ve done something good for my body. It’s possible, of course, that this is just an illusion, but that doesn’t really matter as long as it’s a pleasant one. Second, I hope to become more flexible for martial arts, specifically for kicks: My current flexibility just barely allows me to cleanly execute many types of kicks up to about hip-level. Anything above becomes problematic, because I start hitting the limits for one or more muscle-groups. Of course, high kicks aren’t a necessary ingredient for martial arts, but I’d like some in my repertoire anyway.

This is the second post in the flexibility experiment series. You can find the first post here. In my next post, I will outline my self-experiment with Resistance Stretching.

This post is part of the Flexibility Experiment series.

Part 1: The Problem with Stretching

Part 2: Introducing Resistance Stretching (currently viewing)

Part 3: Method and Benchmarks

Part 4: Q&A with Anne Tierney, Resistance Stretching Expert

Flexibility Experiment, Part 1: The Problem with Stretching Exercises

(Total reading time: 4 Minutes.)

I have practiced different styles of martial arts for most of my life and I’ve been a martial arts instructor since 2000. Part of the training regimen of every style I’ve ever practiced was stretching. In all these years of training, I have never become as flexible as I would like to be, so I decided to do a stretching experiment on myself and see if I can learn something new.

What you Expect vs. What you Get

A long, long time ago, when I first started stretching regularly, I knew practically nothing about it, but had certain expectations none the less. I imagined that stretching regularly would make me more and more flexible. Simple enough, right?

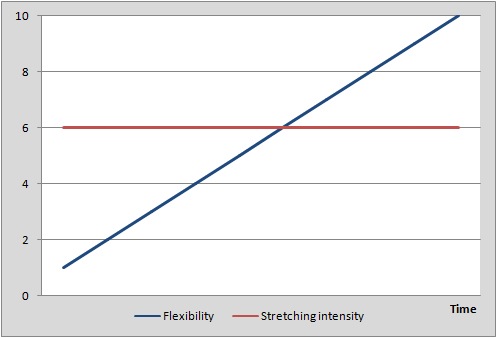

I want to quickly introduce two scales going from 0 to 10, in order to illustrate my point:

- Flexibility Scale: 0 being completely stiff, 5 being able to touch toes and being fairly flexible, 10 being full splits and the kind of flexibility required for acrobats, figure-skaters and the likes.

- Stretching Intensity Scale: 0 being no regular stretching exercises, 5 being stretching on a regular basis (e.g. Yoga-class several evenings a week), 10 being hours of intensive stretching every day.

Here’s what I expected:

I imagined that keeping up a good, steady stretching routine would take me from wherever I was on the flexibility scale all the way to a super-flexible 10, given enough time. Had I thought about this a little more, I would have maybe concluded that I could only reach an 8 or 9 of flexibility unless I stepped up the stretching intensity at some point, but no matter: Both assumptions turned out to be very wrong.

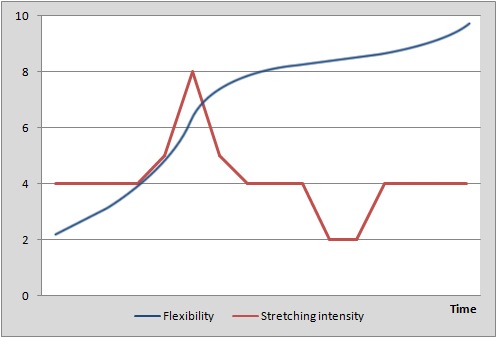

First of all, something initially unexpected but quite natural developed: Over the years of training, my focus changed, my exercise regimens changed and the intensity with which I practiced stretching changed. There were times when I only stretched a few evenings per week, there were times when I stretched every day at home, there was a short period during which I trained Wu-Shu (think of it as Chinese martial-acrobatics) and did very, very intense stretching every day and there were times when I hardly did any stretching at all. Ok, so here’s what that might look like:

Simple: The higher the intensity of exercising stretching, the more quickly I should become more flexible. When I slack off with stretching exercises, I will stop making much progress, but as long as I keep regular stretching a part of my exercise program, I should keep making progress, right? Wrong. Here’s an approximation of what I actually experienced:

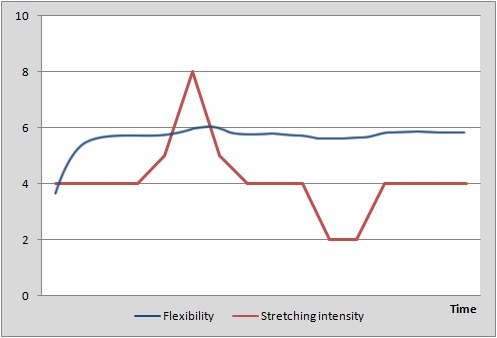

I was already fairly flexible to begin with. When I first started out with stretching, I made progress very quickly. Within a few months, I went from not quite being able to touch my toes (with straight legs, of course) to being able to firmly plant both of my palms on the floor. I saw the same kind of progress for other stretching exercises as well. After that first burst of progress however, I reached a plateau that has remained practically unchanged for years ever since. Extremely intensive stretching exercises budged my flexibility up a tiny bit and slacking off made me lose a fraction of flexibility. By and large, my flexibility seems to be immune to the amount and intensity of stretching I do.

Doing it Wrong

Of course, there are many different ways to stretch and perhaps I have just been doing it wrong? Well, while I can’t claim to have tried every stretching technique on the planet, I have practiced a fair range of techniques. Most of the time, I did stretching exercises that were a mix of Hatha Yoga and “western” static stretching. During the time of practicing Wu-Shu, I did a mix of static and dynamic stretching exercises as well as specific strengthening exercises that were also supposed to increase flexibility. Mostly, I did some stretching before exercising and some afterwards. I have done stretching as an isolated exercise some time during the day and I have done stretching as a part of exercise routines of various intensities.

Common stretching exercises don’t seem to work. I wouldn’t be making such a bold statement based just on my own example, though. As a martial arts instructor, I have seen hundreds of students of all ages doing stretching exercises more or less regularly and more or less intensely (depending on what style they were training). Almost everyone I’ve seen made a certain amount of progress and then reached a plateau. People go from an inflexible 3 to a fairly flexible 5 or from a flexible 6 to a very flexible 9, but I’ve never seen someone transform from inflexible to very flexible, no matter how they trained. What’s worse: Some people seem to be naturally rigid and they make almost no progress by stretching.

Does this simply mean that I and all of my students and peers have been doing it wrong? Perhaps. I haven’t given up hope, though. I recently came across a technique called Resistance Stretching, and it has an approach that is completely different from anything I’ve seen so far. I will introduce Resistance Stretching in my next post and outline the self-experiment I will do with this technique. I, for one, am very eager to see if this will make the crucial difference or if it’s just another fitness-fad.

This post is part of the Flexibility Experiment series.

Part 1: The Problem with Stretching (currently viewing)

Part 2: Introducing Resistance Stretching

Part 3: Method and Benchmarks

Part 4: Q&A with Anne Tierney, Resistance Stretching Expert